About

Climate Friendly Travel

Resources

Contact

Geoffrey Lipman, SUNx Co-founder info@thesunprogram.com

+32495250789

One reason is that the reporting rules for national inventories are a political compromise. They are precise and detailed for rich developed nations, known in U.N. climate jargon as Annex 1 nations. Even if there are gaps, “these are the gold standard, well-resourced and peer-reviewed,” says Peters.But the rules are much less rigorous for developing countries, known as non-Annex 1 nations, which prior to the 2015 Paris Agreement did not have emissions targets. Data submissions from them can be arbitrary, sometimes outright implausible, and are rarely independently checked, analysts note.This even though many “developing” nations, including China, have emissions greater than their “developed” counterparts. As a result, two of today’s three biggest emitters — China and India — as well as oil-rich Gulf states with per-capita emissions higher than any Annex 1 nation, need only comply with the less strict reporting standards.“I would not trust a non-Annex 1 emissions estimate without cross-checking across multiple sources,” says Peters.“The existing patchwork of greenhouse-gas inventories is woefully inadequate,” concluded Amy Luers, director of sustainability science at Microsoft, in a 2022 review with academic colleagues for Nature. They are “rife with measurement errors, inconsistent classification and gaps in accountability.” The situation is made worse, says coauthor Leehi Yona, an environmental lawyer at Stanford University, by “inflexible and outdated” U.N. guidelines for national reporting. Qatar, regarded as the world’s highest per capita emitter, has only filed a formal inventory of its emissions once, with data for 2007.The reasons for the data gaps vary. Some emissions are eminently measurable but are expressly excluded from the U.N. reporting system because there is no agreement on how to apportion them to national inventories. These include international aircraft and shipping, which make up around 5 percent of global emissions.Another category is military activity. It is “one of the most urgent,” says Matthias Jonas, an environmental scientist at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis in Austria. He has found that military fuel use, ammunition firing, and fires set off by bombing during the first 18 months of the conflict in Ukraine caused more emissions than Portugal. Another study estimated that the U.S. military also emits more CO2 than Portugal’s national total.The British advocacy group Common Wealth last year calculated that globally armed forces may be responsible for more than 5 percent of global CO2 emissions. But “we do not have guidelines for estimating these emissions and attributing responsibility,” says Jonas. So, they mostly remain off the books. Another gaping data hole is forest fires, says Yona. Globally, wildfires emit around 1.5 billion metric tons of CO2 annually, more than all but the world’s top five CO2 emitters. Wildfires may be a natural hazard, but in many countries, they are mostly ignited by humans and are often made worse by poor fire management and fuel left in harm’s way. That makes them anthropogenic, she argues. So, the resulting CO2 emissions should feature in national inventories of human-caused emissions. But mostly they don’t.

One reason is that the reporting rules for national inventories are a political compromise. They are precise and detailed for rich developed nations, known in U.N. climate jargon as Annex 1 nations. Even if there are gaps, “these are the gold standard, well-resourced and peer-reviewed,” says Peters.But the rules are much less rigorous for developing countries, known as non-Annex 1 nations, which prior to the 2015 Paris Agreement did not have emissions targets. Data submissions from them can be arbitrary, sometimes outright implausible, and are rarely independently checked, analysts note.This even though many “developing” nations, including China, have emissions greater than their “developed” counterparts. As a result, two of today’s three biggest emitters — China and India — as well as oil-rich Gulf states with per-capita emissions higher than any Annex 1 nation, need only comply with the less strict reporting standards.“I would not trust a non-Annex 1 emissions estimate without cross-checking across multiple sources,” says Peters.“The existing patchwork of greenhouse-gas inventories is woefully inadequate,” concluded Amy Luers, director of sustainability science at Microsoft, in a 2022 review with academic colleagues for Nature. They are “rife with measurement errors, inconsistent classification and gaps in accountability.” The situation is made worse, says coauthor Leehi Yona, an environmental lawyer at Stanford University, by “inflexible and outdated” U.N. guidelines for national reporting. Qatar, regarded as the world’s highest per capita emitter, has only filed a formal inventory of its emissions once, with data for 2007.The reasons for the data gaps vary. Some emissions are eminently measurable but are expressly excluded from the U.N. reporting system because there is no agreement on how to apportion them to national inventories. These include international aircraft and shipping, which make up around 5 percent of global emissions.Another category is military activity. It is “one of the most urgent,” says Matthias Jonas, an environmental scientist at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis in Austria. He has found that military fuel use, ammunition firing, and fires set off by bombing during the first 18 months of the conflict in Ukraine caused more emissions than Portugal. Another study estimated that the U.S. military also emits more CO2 than Portugal’s national total.The British advocacy group Common Wealth last year calculated that globally armed forces may be responsible for more than 5 percent of global CO2 emissions. But “we do not have guidelines for estimating these emissions and attributing responsibility,” says Jonas. So, they mostly remain off the books. Another gaping data hole is forest fires, says Yona. Globally, wildfires emit around 1.5 billion metric tons of CO2 annually, more than all but the world’s top five CO2 emitters. Wildfires may be a natural hazard, but in many countries, they are mostly ignited by humans and are often made worse by poor fire management and fuel left in harm’s way. That makes them anthropogenic, she argues. So, the resulting CO2 emissions should feature in national inventories of human-caused emissions. But mostly they don’t. (The Oak Fire burns near Mariposa, California, in July 2022. DAVID MCNEW / AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES)Thus, California’s wildfire emissions have in some years been as great as those from the state’s power stations. But the state government excludes them from its greenhouse-gas inventories, “even though they are large, measurable, reducible and overwhelmingly caused by human activity,” Yona says.The problem of underreporting is compounded because, according to the public online record, many non-Annex 1 nations have been extremely slow in meeting their requirement to submit inventories every four years. Some backsliders are states at war or with unstable governments. Syria last filed in 2010, Myanmar in 2012, Haiti in 2013, and Libya has never filed. But others have no such excuse. The Philippines last sent its inventory in 2014, and Guyana in 2012.Most startling is Qatar — a major Gulf natural-gas exporter with per-capita emissions widely regarded as the highest in the world. At more than 35 tons of CO2 per person, Qataris emit more than twice as much as Americans. But their government has only filed a formal inventory of those emissions once, in 2011, and provided data for 2007. Since then, Qatar’s actual emissions are thought to have almost doubled.Satellite data shows methane emissions from oil and gas fields globally are around 70 percent higher than governments claim.The UNFCCC web page on reporting rules says: “Without transparency, we are left to act blindly.” But a spokesperson said in an email that the UNFCC had no ability to compel countries to submit timely inventories, which are a “non-mandatory requirement.” Moreover, the spokesperson noted, “most non-Aannex 1 parties face capacity constraints… including those for reporting.” Peters retorted that “Qatar could probably pay a team of 50 people to do the most accurate estimates of emissions ever, but it is not in their interests.”

(The Oak Fire burns near Mariposa, California, in July 2022. DAVID MCNEW / AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES)Thus, California’s wildfire emissions have in some years been as great as those from the state’s power stations. But the state government excludes them from its greenhouse-gas inventories, “even though they are large, measurable, reducible and overwhelmingly caused by human activity,” Yona says.The problem of underreporting is compounded because, according to the public online record, many non-Annex 1 nations have been extremely slow in meeting their requirement to submit inventories every four years. Some backsliders are states at war or with unstable governments. Syria last filed in 2010, Myanmar in 2012, Haiti in 2013, and Libya has never filed. But others have no such excuse. The Philippines last sent its inventory in 2014, and Guyana in 2012.Most startling is Qatar — a major Gulf natural-gas exporter with per-capita emissions widely regarded as the highest in the world. At more than 35 tons of CO2 per person, Qataris emit more than twice as much as Americans. But their government has only filed a formal inventory of those emissions once, in 2011, and provided data for 2007. Since then, Qatar’s actual emissions are thought to have almost doubled.Satellite data shows methane emissions from oil and gas fields globally are around 70 percent higher than governments claim.The UNFCCC web page on reporting rules says: “Without transparency, we are left to act blindly.” But a spokesperson said in an email that the UNFCC had no ability to compel countries to submit timely inventories, which are a “non-mandatory requirement.” Moreover, the spokesperson noted, “most non-Aannex 1 parties face capacity constraints… including those for reporting.” Peters retorted that “Qatar could probably pay a team of 50 people to do the most accurate estimates of emissions ever, but it is not in their interests.”

Even when national returns are up to date and complete, uncertainties abound, says Efisio Solazzo, who studies pollution statistics for the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre in Italy. There are shortcomings in “activity data.” We don’t know, for instance, how much fossil fuel is being burned in many countries, nor how much methane leaks from oil and gas fields and pipelines.

There are also uncertainties in how reliably those activities are converted into emissions estimates. This is normally done using off-the-shelf formulae developed by scientists for the U.N. But critics say these formulae often fail to reflect real operating conditions.

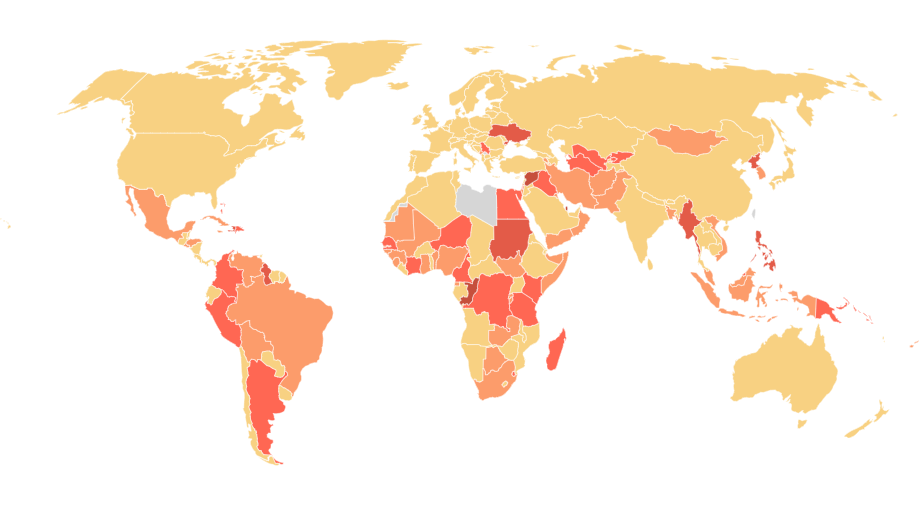

(Source: UNFCCC)

When John Liggio, an air quality researcher at Environment and Climate Change Canada, a government agency, cross-checked his government’s declared emissions from the energy-intensive extraction of the oil sands deposits in Alberta, the results were embarrassing. Aircraft measurements of CO2 in the air above the tar sands suggested that the real emissions were 64 percent higher than those being reported.

Sometimes whole industries are under a cloud. Satellite data analysed by the International Energy Agency (IEA) shows methane emissions from oil and gas fields globally are around 70 percent higher than governments claim, mainly because of unreported leaks and flaring.

The U.S. industry is a major culprit here. Using measurements from hundreds of research flights over well fields, Evan Sherwin, a data analyst at the government’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, found that 3 percent of the methane tapped by American oil and gas wells leaks into the atmosphere, compared to the one-percent estimate used in U.S. inventories.

Globally, there are hundreds of what the IEA calls “super-emitter events” annually, mostly from oil and gas fields. Outside the U.S., many of the worst are in Turkmenistan and other former Soviet states of Central Asia, which often still use decaying and leaky Russian-built infrastructure. One massive blowout in Kazakhstan last year took 200 days to plug.

Governments globally claim forests are soaking up 6 billion tons more CO2 each year than scientists can account for, a study found.

Sometimes the data gaps are more subtle. For instance, standardized emissions factors for burning coal disguise the fact that different types of coal from different places have different emissions rates. Some studies have suggested that the poor-quality coal from many mines in China produce substantially less CO2 than the emissions factors suggest. But other studies suggest the country often burns more coal than it admits to. So, a cloud still hangs over the country’s emissions inventories.

“China is making great efforts to improve the accuracy of its emissions inventories,” says Yuli Shan of Birmingham University in the U.K., who has tracked its data for years. But he notes that an assessment of China’s fossil-fuel emissions by the European Commission’s Emissions Database for Global Atmospheric Research found 23 percent more than recorded in the country’s U.N. submission for the same year.

Concerns about China have increased with the introduction of the country’s carbon trading system, which analysts say could allow energy companies to profit by fiddling the figures. Two years ago, China’s environment ministry found four companies auditing offset claims had routinely tampered with coal samples, doctored test results, concealed energy output data, and provided fictitious verification reports for their power-station clients, so cutting the declared emissions.

(The Wujing coal-fired power plant in Shanghai. RAUL ARIANO / BLOOMBERG VIA GETTY IMAGES)

Away from the energy industry, data discrepancies are often even greater. Emissions from some chemical processes and landfills are poorly assessed, says Solazzo. So are methane emissions from cattle and rice production, while estimates of the global releases of nitrous oxide from fertilized soils could be undercounted by a factor of three.

There may also be previously unconsidered anthropogenic emissions. This month, ecologist Trisha Atwood of Utah State University published calculations suggesting that fishing trawlers that churn up the ocean floor are releasing more CO2 into the atmosphere annually than Great Britain.

Then there are forests. Geographer Clemens Schwingshackl at the Ludwig-Maximilians University in Munich found that governments collectively claim their forests are soaking up 6 billion tons more CO2 each year than scientists can account for. That gap is more than total U.S. emissions from all activities.

The good news is that such ruses in national inventories are under ever greater scrutiny from improved aircraft- and satellite-based data collection. The accuracy of this work is being improved by better modeling of the tracks of pollution through the air and by testing air samples for carbon 14. This isotope, with a half-life of 5,700 years, is ever present in natural emissions of CO2 but absent from the burning of fossil fuels that have been buried for millions of years. NOAA researchers have recently used this to track U.S. fossil-fuel emissions more precisely and say they could do this for other nations too.

But the bad news is that this new data rarely reaches national inventories, which remain stuck in old, often self-serving, ways. While that continues, the data gaps between reported emissions and the actual gases accumulating in the atmosphere will persist. And the world will remain unclear about who is responsible and what is required to meet climate targets.

(By Fred Pearce, Sourced From : YaleEnvironment360)